Theodicy after Auschwitz and the Reality of God

Article Authored By Stephen Gottschalk - (Reposted)

Union Seminary Quarterly Review

Volume XLI Numbers 3 & 4 1987

ISSN 0362-1545

AUDIO NARRATION AVAILABE 🗣

Because Judaism and Christianity are both rooted in God's historical encounter with humanity, they have continually responded to and been shaped by theological dilemmas that have arisen in times of historical crisis. From the emergence of Augustine's eschatology amid the ruins of Rome's North African empire to the Barthian reassertion of God's sovereignty in the midst of the collapse of theological (and political) liberalism during the First World War, seminal advances in Christian thought may be seen in just such terms of crisis and breakthrough. The great risk now is that the crisis of belief which is shaking the foundations of our time may result in a generalized breakdown of faith precisely because a breakthrough has not been attained. This is probable, unless the resources of theological tradition are better used. Since conservative Christian theology generally has not allowed itself even to feel the full impact of these issues, the evangelical tide which has overrun the liberal consensus in the 1970's and 80's may well be seen less as the wave of the future than as the last gasp of the past. In one respect, however, fundamentalists are responding to the current crisis more directly than their opponents: they have realized that this crisis involves issues so basic that weakness and insecurity in confronting them may suffice to invalidate any religious option.

At the heart of this crisis lies the uncertainty engendered by the problem of theodicy after Auschwitz-for which one might substitute not only Dachau or Buchenwald but Hiroshima, Nagasaki and some future all-but-unimaginable nuclear holocaust as well. Elie Wiesel's first anguished reaction to the sight of children burned alive at Auschitz is echoed, even if faintly, in the hearts of all those who have allowed themselves to experience this crisis by feeling something of the pain that is so much a part of the contemporary world: "Never shall I forget those moments which murdered my God and my soul and turned my dreams to dust. Never shall I forget these things, even if I am condemned to live as long as God Himself. Never."

This is not to say that God "died" for him at that moment. Rather, as Wiesel himself has said, he was then confronted with the specter of a God who did exist and yet could permit the existence of such horror. As Robert McAffee Brown put it, "Ever since that first night, Wiesel has struggled with two irreconcilable realities the reality of God and the reality of Auschwitz. Either seems to cancel out the other, and yet neither will disappear. Either in isolation could be managed-Auschwitz and no God, or God and no Auschwitz. But Auschwitz and God, God and Auschwitz? That is the unbearable reality that haunts sleep and destroys wakefulness."

Brown's statement of the situation, extreme though it appears, is faithful to Wiesel's perceptions, just as these perceptions apply to the situation that confronts us. In the wake of Auschwitz and all that it has come to mean, the problem of evil can no longer be stated, much less solved, in less than categorical terms. The classic formulation of the issue of theodicy now translates itself into two stark alternatives: atheism-no God at all-or a concept of both God and evil radically different from anything that the Christian tradition has fully reckoned with before. It has become morally intolerable and theologically impossible that the two can exist-in the same sense of the term "exist"-at the same time.

This point can now be said to apply not only to the moral evil which Auschwitz incarnates but to "natural" evil (floods, famines, earthquakes) as well as "metaphysical" evil, the human consciousness of finitude itself. Auschwitz has magnified the problem of evil, compromising earlier compromises, making working solutions un workable and avoidance of the issue impossible. The Holocaust encompassed the inconceivable evil of six million deliberate murders. What, then, should be said of an equally deliberate design which has caused the death-often accompanied by great suffering-of every living creature which has ever died from "natural" causes?

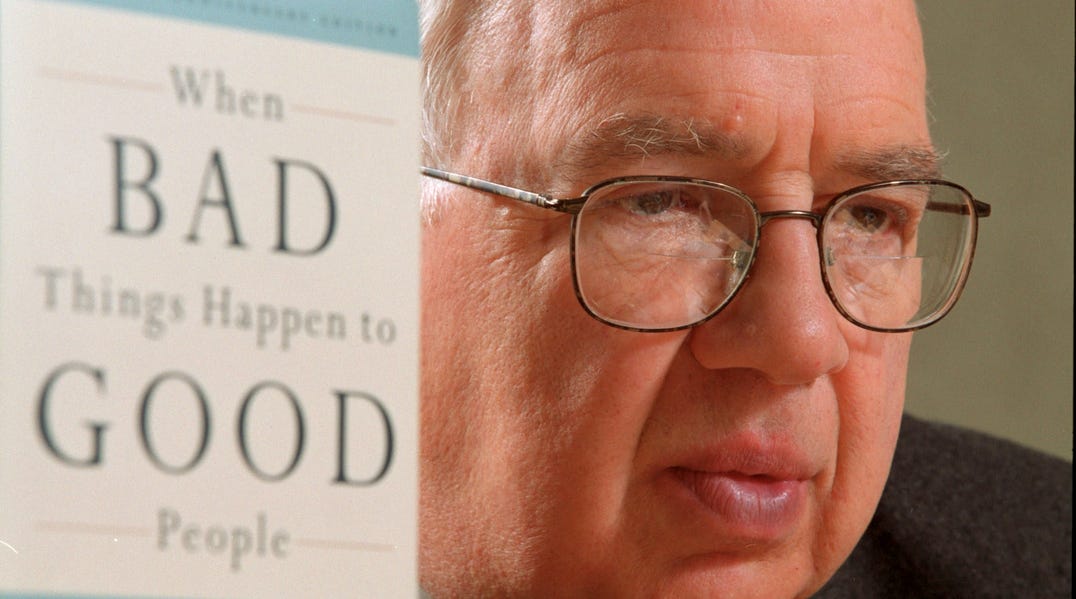

In the wake of Auschwitz, any middle ground on this issue is increasingly slipping out from under us. This may well explain the growing appeal of the view of God, articulated in process theology as well as in Rabbi Harold S. Kushner's When Bad Things Happen to Good People, as loving and good yet limited in his sovereignty.

This concept of a finite but loving God, working alongside humanity to mitigate pain but unable to prevent it, has been waiting in the wings for nearly a century since William James first proposed it in A Pluralistic Universe in 1909. It was given intellectual substance through the assimilation of insights from the work of Whitehead and Hartshorne into process theology, which envisions God in pantheistic terms as coextensive with the active, unfinished process of human life. But it was Kushner's timely book, for some time a best-seller and now translated into a number of languages, that touched a religious nerve in popular thought in a way that most theological studies cannot.

One suspects, however, that the idea of a limited God has not gained temporary currency on its theological merits. Its appeal lies rather in the fact that it satisfies a desperate longing for the resolution of a situation that will not go away. While it may look like a middle-ground compromise solution to the problem of theodicy, it involves a drastic jettisoning of the element of God's sovereignty traditionally considered indispensable to Christian faith - a point made abundantly plain by the title of Charles Hartshorne's recent book Omnipotence and Other Theological Mistakes. In this respect, it resembles a decision for divorce in a marriage which has long since become unworkable and in which compromise solutions have lost even the appearance of effectiveness. For many, the theological implications of recent history have simply invalidated earlier compromise solutions. The classic view that evil arises out of human moral freedom without which our love of God would have no meaning, along with the more conventional evangelical concept of the experience of evil as a divinely ordained school for the nurture of Christian virtue, may well prove to be among the theological casualties of our time. What, some have asked, can we say about a God who would construct a situation in which human moral freedom could lead to suffering on such a scale as the very word "Auschwitz" has come to symbolize? Would not a God who teaches such expensive lessons or fashions creatures in need of learning them be morally worse than His worshippers? Such "solutions" still persist and are even assiduously pursued in theological reflection in both the popular and academic realms. But after Auschwitz their advocates may increasingly sound like Job's friends: well-intentioned but ineffectual because painfully out of touch with the situation. Nor are they likely to be believed. Assuming that we are unwilling to deny God's existence or redefine it to the point that God no longer remains God, how can we think about theodicy after Auschwitz while remaining faithful both to the Gospel and to the painful lessons of recent historical experience?

II

The approach to the problem of theodicy in process theology may have its element of pathos. Yet one can hardly find fault with its logic within the parameters of the problem of evil as it is bound to be felt in the present situation. But when the limits of both logic and insight have been reached, a new direction can often be found only through a radical revisioning of the problem. This may be what process theology has attempted. Yet it has not critically assessed an assumption more or less concealed within various formulations of the problem: that God and evil both exist in the same sense in fact and as fact. Most discussions of theodicy assume the factual nature of evil-an assumption which makes the problem all the more intractable. To take a recent major example, John Hick's closely-reasoned study Evil and the God of Love formulates the dilemma suggested in its title this way: "If God is perfectly good, He must want to abolish all evil; if He is unlimitedly powerful, He must be able to abolish all evil: but evil exists; therefore either God is not perfectly good or He is not unlimitedly powerful." Hick goes on to define theodicy as "the defense of the justice and righteousness of God in the face of the fact of evil."

This definition and Hick's statement of the problem presume that the experience of evil is just what it appears to be: an unchallenged reality against which other realities are to be measured. Yet is the same factual quality, a quality of unmistakable authenticity and concreteness, attributed to humanity's experience of God? Here is the crux of the problem, which turns out to be not so much the problem of evil in its classic formulation as that of the immediacy of this God-experience and the evaluation of its meaning.

Paradoxically, the usual statement of the problem of theodicy implicitly assumes that there can be no God-experience, or that it can be dismissed as so "subjective" that it is extraneous to any theological discussion. Accordingly, the empirical reality of evil is held to be indubitable but that of God questionable. On the other hand, when an individual does have an intense God-experience, the problem of evil begins to recede as a stumbling block to faith. The implicit presupposition upon which the statement of the problem rests is that of the conclusiveness of the experience of evil and the inconclusiveness of the experience of God. But when this experience is unquestionable, that supposition is not made.

We have scarcely begun to inquire what could happen if the problem of evil were addressed from the standpoint of a renewed God-experience. One thing is clear: doing so would mean taking a radically different approach from most treatments of the problem-especially given the magnitude of the manifestations of evil in the twentieth century. One might, of course, adopt a dualistic view, positing the existence of evil as such. But if this position is not adopted, theodicy today is increasingly likely to adjust its concept of God to the degree that the fact of evil becomes more momentous. If God and evil both exist in the same sense of the term, what alternative remains but to bargain away either divine sovereignty or divine goodness in order to resolve the dilemma posed by God's presumed coexistence with unspeakably great evil on a mammoth scale?

In fact, this is what has increasingly occurred in the development of theodicy after Auschwitz. Taking a different direction would move us either back into earlier Christian tradition or forward beyond the point where the mainstream theological consensus is presently located. For to the degree that the unquestioned reality of God is asserted on the basis of the concrete God-experience, the status of evil as unchallengeable fact must again be brought into question.

This approach to the problem leads naturally to a revisioning of evil in privative terms as ontologically "nothing," an idea most influentially developed in the Christian tradition by Augustine. This position continues to be widely supported within the Christian tradition. But the initial impulse that gave rise to it has been for the most part, lost. For Augustine, that impulse was a profound and heartfelt insistence upon a God so ultimate in sovereignty and love that no compromise of either was possible. One of the most significant tasks facing contemporary theology is to transpose this impulse into the context of the present. Some heirs of the Augustinian tradition tacitly acknowledge that evil, since it has no source in God, can be regarded only as a perversion or disruption of God's good creation, therefore as ontologically nothing. What would be the result of adopting this view with a radicalism and consistency commensurate with the extremity of the contemporary situation, while retaining the integrity of Augustine's initial insistence upon the reality and sovereignty of God?

III

The only mainstream theologian of our time who begins to answer this question is Karl Barth. Indeed, his prolonged meditation on the theme of "das Nichtige" constitutes one of the most controversial and misunderstood sections of Church Dogmatics. It should be clear at the outset that for Barth as for Augustine, an insistence upon the nothingness of evil is no mere verbal ploy intended to avoid the issue while pretending to resolve it. It results directly from the assumption of the unchallengeable reality of one absolute God that pervades the tradition reaching back from Barth through Calvinism and Puritanism to Augustine.

Recent theology might well have adopted such an approach to the problem of evil, in which theodicy is at the service of theology and not vice-versa. For the most part, however, Barth's treatment of the problem has been subject to strong criticism, largely on logical grounds, when appraised alongside other "solutions" to the dilemma of theodicy. Such criticisms, while understandable, miss the vital point that Barth is not "doing" theodicy from a purely "logical" standpoint. He simply will not concede some privileged position of philosophical neutrality from which one can consider the problem without a commitment to (or against) the truth of the Gospel-a commitment that must decisively affect one's conclusions. For him the only valid approach to the problem of evil is "dialectical." It must not aim at a neat abstract "solution" but must be just what the term "approach" implies: a coming at the problem from a standpoint which recognizes one's place within human experience and does not pretend to a privileged position outside it. "We have not sought to apprehend the relationship between Creator and creature philosophically and there fore from without," Barth writes, "but theologically and therefore from within. Hence we have not accepted the alternatives posed by an abstract and external view.” He does not move from the problem of theodicy back to the understanding of God; rather, he moves out from the conviction that in the light of the revealed and experienceable reality of a sovereign and good God, evil must be described-both with respect to its ontological status and its operative character-in terms of its sheer negation, as what he calls "das Nichtige."

This all but untranslatable term, which is rendered "nothingness" in the English translation of the Church Dogmatics, points to that which God the Creator passes by, does not choose to create, refuses to bring into being. Yet it is not a mere zero or vacuum, since "das Nichtige" for Barth suggests the operation or action of menacing negativity. It is the element of chaos, meaninglessness, and formlessness which, having been rejected by the sovereign God and remanded to non-being, stands poised to threaten the perfection and wholeness of the creation God has called into existence. For this reason Barth entitles his chapter on the subject "The Reality of Nothingness" and asserts unequivocally before launching into his discussion that "Nothingness is not nothing."

Indeed, nothingness has what can be called a structural necessity within his doctrine of creation. Since human beings and all facts within the natural order exist as created entities, brought out of nothingness into living being by the Word of the Creator, their very status as creatures keeps them "on the very frontier of nothingness.... It belongs to the essence of creaturely nature, and is indeed a mark of its perfection, that it has in fact this negative side ... " -or what Barth in a powerful (if potentially evasive) metaphor calls "the shadow side of creation." It is by means of this concept of the negative or "shadow side" of creation that he integrates his understanding of natural or "metaphysical" evil into his theology.

Again, this "shadow side of creation" is not to be construed as nothingness but as the limitation and finitude which are integral to creatureliness. As Austin Farrer put it in an argument closely related to Barth's, "Because we take the physical creation to be good, we are outraged by the presence of certain distressing features in it; but once they are proved inseparable from its general nature, there is no further question we can rationally ask." Pain, physical suffering, even death itself must then be seen as structured into the way God has ordered creation, "For all we can tell," writes Barth, "may not His creatures praise Him more mightily in humility than in exaltation, in need than in plenty, in fear than in joy, on the frontier of nothingness than when wholly orientated on God?"

In other passages, however, Barth approaches the problem of evil differently, since he is aware that viewing pain and death as necessary aspects of creaturely existence may not be sufficient-at least from the standpoint of the suffering creature. At times he speaks of creaturely existence to which we should be reconciled, but as expressions of the malevolence of das Nichtige. Sickness thus becomes "a forerunner and messenger of death ... an element in the rebellion of chaos against God's creation. It is an act and declaration of the devil and demons ... in that neither is it good nor is it willed and created by God at all, but is real and powerful and menacing only as part of that which He has negated." Understood as an aspect of man's punishment for sin, it is "the executor of God's final sentence-to the man who has fallen from God and become His enemy."

Which of these two interpretations of suffering expresses Barth's basic view point is difficult to determine. Probably Hick is correct when he writes that "if we were to ask Barth whether disease and bodily pain fall within the shadow side of existence, or represent hostile acts of das Nichtige, he would presumably reply that whilst ideally they are merely part of the negative, but innocently negative, aspect of creaturely life, yet concretely, as they occur within our sinful human experience, they have become manifestations of das Nichtige."

A clue to Barth's most basic impulse is that in those often impassioned passages where he speaks of the work of Jesus Christ in defeating the power of nothingness, physical suffering and pain are portrayed explicitly as expressions of das Nichtige. In Jesus, he writes, "there speaks and acts the one who for the salvation of the creature and the glory of God has routed nothingness and the total principle of enmity, physical as well as moral"; if Jesus were not "Saviour in this total sense, he would not be the Saviour at all in the New Testament sense." Indeed, at one point in discussing Jesus' saving work, Barth goes so far as to say that "in the physical evil concealed behind the shadowy side of the created cosmos we have a form of the enemy and no less an offense against God than that which reveals man to be a sinner."

This statement brings more clearly into view the underlying ambiguity in Barth's handling of the problem of evil and suggests a different approach to the problem. Are sickness and pain to be accepted as inherent in creation as God intends it? Or are they to be taken as expressions of nothingness against which Christians are bound to protest? If the former, then sickness and physical pain are grim necessities of human existence, inasmuch as they are structured into the God-ordained finiteness of the creature. If the latter, then they are to be understood as manifestations of evil and epiphenomena of sin, and therefore should be overcome as part of humanity's redemption from both.

IV

The view that sickness and physical pain are manifestations of evil which will eventually be overcome by redemption is central to a doctrine which Barth took pains to comment on and reject in a lengthy footnote in Church Dogmatics: Christian Science. The footnote is located in the very section of the Church Dogmatics in which he most clearly identifies sickness and pain as forms of nothingness. And Barth does acknowledge that Western Christianity, especially Protestantism, had "too long succeeded in minimizing and devaluating" the healing ministry of the Gospel. Yet he was extremely uncomfortable with the theological position underlying the Christian Scientists' consistent and determined efforts to restore its practice.

As we might expect, Barth's comments on this controversial teaching were far more insightful than the ill-formed opinions which had clouded theological assessment of Christian Science in its American context. The reason can be found largely in the fact that as source material for his comments, which ran just under 1000 words, he relied almost exclusively upon a much more extensive article entitled "Der Szientismus" by the eminent German church historian Karl Holl. First published in 1915 after the Christian Science movement had gained substantial public attention in Germany, Holl's account, while critical, is remarkably free of polemic. The text contains some small factual errors concerning matters about which Holl was not in a position to be better informed, but it is for the most part theologically accurate. Rudolf Otto commented that it was "absolutely the best" treatment of Christian Science he had read.19 And Barth spoke of Holl's article as a "careful study" which did "Mrs. Eddy almost too much justice."

Fortunately, Barth saw fit to rely upon it in framing his own critique, except in his introductory comments. Before mentioning Holl's text, he declares: "the tenet that sickness is an illusion is the basic negative proposition which in the seventies of the last century the American Mary Baker Eddy said she did not lay down but 'discovered.' ... This is in fact not the case, as a reading of Holl's text in conjunction with Eddy's writings shows. While the healing of sickness is a vital practical outcome of Christian Science, Holl is right in saying that Eddy lays "stress on the fact that to her as to the rest of Christendom healing is not the most important element of Christianity. The main thing to her is the battle against sin, the healing being only an attendant though indispensable result."20 Barth himself concedes that "even Mrs. Eddy" asserts the priority of healing or "dissolving of the false appearances" of sin to the elimination of sickness and death.

Moreover, for Mrs. Eddy, none of these "false appearances" is an "illusion" in the conventional sense of the term - the sense in which Barth had employed it when, just prior to discussing Christian Science, he spoke scornfully of the view of sickness as the product of mere "imagination." Eddy did not believe that sickness was imaginary whereas other human phenomena were not; rather, she saw it as one of many constituent parts of the human condition. Her departure from Christian orthodoxy lies in the fact that she saw mortality itself as the consequence of sin in the broad Christian sense of alienation or separation from God, for the category of "sin" included the arrogant denial of God's supreme reality which eventuates in what she called "the atheism of matter."21

This conclusion can be understood as a radical answer to the problem of theodicy-though not one which originated in theological reflection or was wrought out in formal speculative terms. Eddy's particular resolution of the problem grew essentially out of the impulsion of her own religious experience. One can see it germinating in her early rebellion against the stern, wrathful God of her father's predestinarian Calvinism and taking root in her later struggles with the question of how a God of love could have constructed the conditions of a life as wretched as hers became. 22 Her "discovery" of Christian Science, which she believed occurred in the context of a healing experience in 1866, can be partially understood against the background of her rebellion against Calvinism. But as recent investigation of her roots in the tradition of New England Puritanism has shown, her real theological motive was linked to the rigorous Augustinian and Puritan defense of God's absolute sovereignty and goodness which refuses to ascribe evil in any form to a God who is wholly good.23 The iron logic which led Calvin from the passionate insistence upon God's sovereignty to the "horrible" doctrine of predestination led her to the very opposite conclusion: that God's infinite goodness precluded evil from being anything other than the temporary effect of the failure to apprehend His reality in its fulness.

For Eddy, it was idolatrous and a fatal compromise with materialism to believe that the God who gave life-who in the ultimate sense constitutes our life-could be reduced and confined to a finite form limited by matter. Hence she maintained that, by virtue of God's infinitude, "the spirituality of the universe is the only fact of creation."24 When she spoke of God in her mature theology as "All," it was not in some vaporous metaphysical sense that denied humanity's distinct existence or the possibility of our encounter with "the infinite Person whom we worship".25 Her intended meaning was that the reality of God denies ontological reality to whatever denies God-including, as she thought, the evils which conventional theological opinion attempted to account for, but which Jesus commanded his followers to heal. With no hesitation and apparently some relish, she drove home again and again what she saw as the fatal weakness in the theodicy of orthodox Christianity: the belief that a God who was wholly omnipotent and good could be responsible for conditions of sin and suffering. "God is not, cannot be, the author of experimental sins," she declared characteristically of the classic "free will defense," on which she also commented elsewhere: "Would any one call it wise and good to create the primitive, and then punish its derivative?" On the broader question of natural or "metaphysical" evil she wrote in a passage echoed by many others that to "regard God as the creator of matter, is not only to make Him responsible for all disasters, physical and moral, but to announce Him as their source, thereby making Him guilty of maintaining perpetual misrule in the form and under the name of natural law."26 For Eddy, the Science which opposed these assumptions insisted on submission to God's logic wherever it led; and it led, she believed, to a radical but rational challenge to the evidence of the senses. For its result was the practical transformation of the very situation to which they testified-that is, to the healing of sickness and sin, and the restoration of the power of primitive Christianity. Her aim was not to account for the origin of evil in a logically satisfactory way but to define a new standpoint from which it could be overcome, or reduced, as she once put it, "to its native nothingness."27

Critics of Christian Science have often pointed out that Eddy's approach to the problem of evil docs not deal with the question of how the very illusion of evil could be possible in a universe created by God. They have therefore argued that she merely shifted the terms of the discussion, substituting evil as illusion for evil as fact. Indeed, as philosopher Ralph Barton Perry once observed, the traditional Christian responses to the problem of evil could really go no further than to modify the statement of the problem in just such a way.28 If Eddy's theology is carefully scrutinized, however, it becomes apparent that she was well aware of this criticism but consciously made no attempt to provide a theoretical answer to it. For her the question of evil could only be answered at the existential level of the demonstration of the sovereignty of God through the act of reducing evil to its "native nothingness". The only terms in which the problem of evil can be resolved are therefore inseparable from the actual process through which evil is destroyed. From this standpoint, speculation about the origin of evil as an illusion or "belief" is by no means neutral but presupposes credence in the belief. Far preferable to such speculation would be the unqualified acknowledgment of God's absolute sovereignty. For the effect of this acknowledgment would be the amelioration of the conditions of pain and suffering which occasion the raising of the problem of evil to begin with. Eddy, therefore, was perfectly willing to admit what she called "the awful fact that unrealities seem real to human, erring belief, until God strips off their dis guise."29 But this admission for her by no means merely restated the problem of evil in different terms. It pointed to the need of shattering the illusion that evil has any objective existence or necessity. The means of redemption must therefore include the recognition of evil as nothing other than the sinful error of life and mind apart from God-an error that Christians needed not to account for, but to overcome.

If Eddy looked for any explanation of the origin of evil at all, it was in the limitation of the human mind and, accordingly, in a broadening of the Christian concept of sin. If one grants that humanity is "fallen" and in sin (a proposition quite congruent with her theology as far as human beings are concerned) then it is natural to assume that the human perceptual faculties are fallen as well. In this "fallen" state, we are simply unable to discern creation as God intends it. What human beings "see" is therefore only what their own perceptual limits enable them to see. This does not deny the reality of the universe of daily experience, but it does mean that materiality and destructiveness are not inherent in God's creation. Rather, the sinful error of life apart from God operates through the presumed authority of "natural" law and material perception, blinding humanity to the supreme reality of God's Kingdom, which is spiritually present to be brought to light. So hypnotic is this basic error of mortal or carnal mindedness that it required the revelatory breakthrough of Jesus' life to make possible humanity's recognition of the encompassing spiritual reality to which conventional perception remains blind. Eddy saw his life as a unique revelatory incursion into the perceptual limits of human experience of an authentic spiritual existence which defines the true being of all men and women as the sons and daughters of God.

To accept the implications of this revelation-in which Jesus' triumph over death is central-is therefore to accept the fact that ordinary perception is really seeing "through a glass darkly." It is to recognize that to live out the ordinary material appraisal of existence is to dwell within an illusory sense of what experience now holds as possible. But adopting a term from her New England Edwardsian heritage, Eddy held that through "spiritual sense" God's presence could become so tangibly apprehended that evil and its effects could be gradually displaced in human experience. Thus they could be shown to be inherently insubstantial effects of the radical human failure to live in terms of the presence of one absolute God.

In effect, Eddy deals with the problem of evil by claiming that it isn't possible to solve it within a cosmology that sees God as the creator of a physical, finite world in which suffering inheres by the very nature of mortality. Thus, what traditional Christianity saw as a heavenly or ideal realm in the beyond, Eddy insisted already exists as the order of spiritual fact, God-created and God-sustained, to which limited human perception is sinfully and ignorantly blind. Just so, the spiritual condition which orthodoxy holds may be gained in an afterlife Eddy sees as the "scientific", or actual and authentic, nature of humanity in the present. Apparent materiality is just that: the appearance within the sense of life alienated from God of a pervasive human failure to understand divine infinitude and the actual relation of God to creation.

V

Barth's critique of this position is illuminating, not only for what it says about his own theology but for what it implies about the alternatives for theodicy in our time. He follows Holl in identifying the error which Eddy saw as basic to mortality as a "forgetfulness" of God which leads to the "appearances" of sin, sickness, and death. He also rightly observes that for Christian Science "Jesus was and is the embodiment of truth which scatters and breaks through the mist of these false appearances." Yet he minimizes as Holl does not Eddy's insistence that regeneration from these false appearances requires, in her words which Holl quotes, "taking up the cross and following Christ in the daily life."30 Though conceding that Christian Science has several features derivative from the New Testament, Barth is finally unwilling to concede it a place within Christianity.

Here his departure from Hall's formulation and emphasis is revealing. Holl had contended, as Barth notes, that the "positive position of Christian Science can be considered correct from a Christian viewpoint: That God is really the source of all reality." In differentiating his own theology from Christian Science and in denying its Christianity, Barth agrees that "God is indeed the basis of all reality. But-and here is the decisive point for him-"He is not the only reality. As Creator and Redeemer He loves a reality which is different from Himself, which depends upon Him, yet which is not really reflection nor the sum of His powers and thoughts, but which in face of Him has an independent and distinctive nature and is the subject of its own history, participating in its own perfection and subjected to its own weakness."

Eddy, of course, had never maintained that the infinitude of God denied the distinctive identity of creatures. But she did insist upon the qualitative continuity of creation with God. She thus categorically refused to admit that the underlying or "scientific" reality of creation can be separate from its spiritual source. The belief that they are qualitatively separate was the quintessential error and giant sin which lay at the root of all the evils in human experience. In stark contrast to this position, Barth views the ontological discontinuity between Creator and creation as actual and imposed by God. The negative or "shadow side" of creaturely existence "really belongs to God's good and perfect creation." In support of this contention, Barth reiterates the traditional argument pointing to Jesus' advent in the flesh as clear cut proof that God creates and sanctifies the material creaturely state-a proof which should force us to abandon "the obvious prejudice against the negative aspect of creation.... In the knowledge of Jesus Christ," he declares categorically, "it is inadmissible to seek nothingness here."31

VI

The theology of Christian Science has not generally been given significant attention within theological circles, with the notable exception of Holl's and Barth's appraisals. Yet it has not only been embraced by tens of thousands of adherents over the years but embodied through their commitment to spiritual healing-a commitment which has been increasingly shared by other Christian bodies. If any one belief unites those who are presently involved in this practice, it is the conviction that God's will is against rather than for disease and the suffering it entails. The growing agreement on this point may itself be said to constitute an incipient theodicy that has far reaching and perhaps unfathomed implications for theology. The healing practice of Christian Science proceeds from just this view of God's relation to human suffering. Indeed, by virtue of its very radicalism on this matter, Christian Science defines options and raises questions which have not been settled and which could hardly be so well articulated if its approach to theodicy is not taken into account. One needs to be neither a Barthian nor an advocate of Christian Science to grasp the significance of these questions and to begin thinking about them in different terms from those in which the problem of theodicy has too long been addressed. The need is clearly to open new views of old problems that have become more acute even while they continue to defy solution. And it is often in corners remote from the current mainstream that significant leads are likely to be found.

In the light (or perhaps the darkness) of twentieth century experience, perhaps the largest question to which this line of inquiry leads is the following: How is it possible to maintain the reality of God as well as a different sort of reality (as does conventional Western, Christian cosmology) and, at the same time, satisfactorily solve the problem of theodicy? On the basis of a rigorous defense of the sovereignty and goodness of God, Barth goes as far as he can in the direction of treating evil as nothingness within the world-view of Western Christianity, which in the final analysis he defends resolutely and which Eddy just as resolutely challenges. But can the dilemma of theodicy after Auschwitz be honestly confronted without bringing this world-view radically into question?

If pursuing an answer to the dilemma of theodicy today within the structure of traditional cosmology can only lead to a dead end, where lies the possibility for renewal? The raising of this question may itself bring us face to face with the fact that the agenda of theology--more specifically theodicy-has not really been the agenda of the Gospel. The road out of the present impasse may well lie in giving renewed priority to the Gospel's demands. It can no longer be seriously questioned that the thrust of the Gospel lay in Jesus' proclamation of the Kingdom of God nor that this proclamation had both a present and a future aspect. It pertained not only to the expectation of an apocalyptic cataclysm in the future but to the new reality made visible through Jesus' presence and acts. The new reality of the Kingdom dispelled the ordinary patterns of experience-its priorities, obligations, and even its temporal conditions. Here the parables themselves, with their frequent pattern of the reversal of the normal and expectable in human life, can be seen as confirmed and extended by the supreme "parable" of Jesus' own life. For that life "reversed" everything which is conventionally regarded as a part of human experience-relational as well as physical even while offering an unparalled example of humanity in its fullest sense.

Jesus brought the new reality of the Kingdom into the midst of present experience, obviating the very question of theodicy by refusing to concede the existence of a realm from which God's active supremacy did not demand to be acknowledged. That he contested the grounds of present experience for the Kingdom of God is evident in his own statement of the meaning of his healing works: "If I by the finger of God cast out demons, then the Kingdom of God is come unto you." One could say that the Kingdom is come unto, or penetrates, the present condition of human suffering disposing not only of the question of theodicy but of its premise. For this premise, after all, presumes the absence of the very God whom the Gospel proclaims as absolute and sovereign in His presence so much so that the presence of God and the presence of His Kingdom are the same presence. Jesus' own answer to the problem of theodicy, then, lay in the very fact that he lived, as John Cobb put it, "in the white heat generated by the nearness of God." Speaking of the intensity of Jesus' experience of God, Cobb further writes: "He knew God as the present active reality that had incomparably greater reality than the world of creaturely things. He lived and spoke out of the immediacy of this reality.. . . Hence the Kingdom was at hand and, indeed, at hand in such a way as to be already effectively operative in the moment."33

Given the critical spiritual situation of our time, how else can we avoid a theodicy that is a mere intellectual exercise but by drawing nearer to that fire-source? May not the only possible advance in theodicy lie in taking more seriously than ever before and without qualification-yes, without turning back to bury the dead-the demands of accepting the Kingdom in its fullness? This was, after all, the very requirement that Jesus imposed on his disciples. If God, the sovereign God whom Jesus proclaimed, were understood without compromising qualification to be absolutely real, this would be not only a possible way to solve the dilemma of theology. It would be the only way to solve it, for it would be the only possible way to a radical redefinition of the problem.

This, of course, is a very big - if one which points again to the fact that the sources of renewal in theology must lie in the depths of Christian experience. In this renewal lies the only possible response to the dilemma of theodicy after Auschwitz. The ultimate impact of the Holocaust was to create a horror so great as to bring radically into question the idea of the reality of a God in whose world it could occur. With what more savage irony could that purpose be effected than by simultaneously trying to obliterate the people who claimed to be chosen by that very God?

If this were allowed to happen, then the Holocaust as symbol would have an even more destructively demonic impact on humanity than the Holocaust as fact. The only way to deal with its effects would not then be merely to hang on to the shreds of faith that remain. It would be to reverse all that its magnification of evil would accomplish by moving, not back, but forward into a magnified understanding of the reality of God.

NOTES

SOURCE LINK: https://www.johnsonfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/gottschalk-theodicy.pdf

l. Elie Wiesel, Nif!,ht (first published as La Nuit, 1958). (New York: Avon Books, l %9), p. 44.

• Robert Mci\fec Brown, fi/ic Wiesel: Messenger To All Hum,m,tv (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1983), p. 54.

• William James, A I'luralistic Universe (London: Longmam, Crecn, and C:o., 1909), pp. 311-313.

• One possible alternative is advanced by Harold M. Schulweis in his recent study Lui/ and the Morality of Cod. Schulweis argues for a strategy whereby to deprive the critics of religion of the "loaded options" built into traditwnal statements of the alternatives for theodicy. For such a "predicate" theology, the critical question becomes, not the existence of God, bur the possible godliness of modes of human

existence. However valid this line of inquiry, however, the humanization of the question of theodicy does nothing to diminish the urgency of addressing it.

• Charles Hartshorne, 011111ipote11ce and Other Theological Mistakes (Albany, NY; State University of New York, 1984).

• John Hick, Evil and the God of Love (New York: Harper and Row, 1966), pp. 5,6.

• Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, English translation by G. W. Bromilcy and T. F. Torrance (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark), Vol. Ill, 3, pp. 293-368.

• See, for example, the treatment of Barth's position in George Henry's article "Nothing" in Theology Today (Oct., 1982), pp. 274-289; also the critique in Hick's Evil and the God of Love, pp. 141-150.

• Barth, Dogmatics, III, 3, p. 366.

• Barth, Dogmatics, Ill, 3, p. 349.

• Barth, Dogm<1tics. Ill, 3, p. 296.

• Austin Farrer, Loue Almighty and Jlls Unlimited, (Libraire Payot, 1946), p. 66. Ll. Barth, Dogmatics, Ill, 3, p. 297.

• Barth, Dogmatics, Ill, 3, p. 366.

• Hick, fui/ ,md the God of Love, p. L\8.

• Barth, Dogmatics, III, 3, .BI, p. 3 15.

• Barth, Dogmatics, 111, 3,311. All quoted comments by Barth on Christian Science arc from the text of the note in Dogmatics, III, 4, pp. 364-65.

• Karl Holl, "Der Szientismus," reprinted in Gesammelte Aufsaetze Zur Kinhengeschichte (Tubingen, 1921-28), Vol. 111, pp. 460-479.

• Rudolf Otto, "Der Szientismus," Theologische Literaturzeitung ( 1918), columns 14 and 15.

• Holl, "Der Szicntismus," p. 470.

• Eddy, Science and Health with 1'ey to the Scriptures (Boston, MA: Christian Science Publishing Society, 1911), p. 580.

• For a dose analysis of Eddy's early years, particularly her religious development, see Robert Peel's

Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Discovery (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston 1966).

• A detailed study of the bearing of Calvinism on the development of Eddy's thought is the doctoral dissertation by Thomas C. Johnsen, Christian Science and the Purit,m Tradition, John Hopkins University (1983).

• Eddy, Science and Health. p. 471.

• Eddy, The first Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany (Boston MA: Christian Science Publishing Society, 1913), p. 192.

• Eddy, Science and Health/th, pp. 230, 356, and 119.

• Eddy, Science and Health, p. 91.

• Perry's observation on this point was related to me by Robert Peel, who worked under Perry as a graduate student at Harvard.

• Eddy, Science and Health p. 472.

• Holl, "Der Szientismus," p. 470. The reference is from Science and Health. p. 179. 3 I. Barth, Dogmatics, III, 3, p. 30 I.

• Eddy, Science and Health, pp. 525,561.

• John Cobb, Jr., The Structures of Christian Existence (New York: Seabury Press, 1979), pp. 115,

112-113. I am aware that as a process theologian, Cobb would hardly share the conclusions of this essay-much as this and other comment., from his rcnwrbhle book .seem to me to point in their direction!